The Sun Stands Still, Stars Fall, and Worlds Collide

December 10, 2020

Hello star-gazers! Time to prepare for an eventful couple of weeks!

But first...did anyone watch the penumbral eclipse? Here's my report: I had never seen one in person before, so I (somewhat reluctantly) set my alarm clock and looked out my window at 3:30 AM. If I hadn't known what was going on, I would have assumed it was just a normal full moon. There was certainly no “shadow” or obvious dark part. But when I made a conscious effort to compare how brightly each side of the moon was shining, I could tell that one side wasn't quite as brilliant as the other, as if someone had turned down the dimmer switch a little on that side. (If I remember correctly, this eclipse peaked at about “70% immersion”—sometimes the moon goes deeper than this into the penumbra, and closer to the umbra, and then the inner edge is more faded and easier to notice.) When I checked a live video feed on the internet, I saw that I had identified the dimmer side correctly. It was very obvious in the video—it looked like whoever had his hand on the dimmer switch had turned one side of the moon completely off. (The video broadcasters must have been using digital enhancement...cheaters!)

Anyway, this month we have a few solar system events to watch for along the zodiac, including a historic conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, plus a couple of meteor showers, including one of the best of the annual showers. Here is a brief list of highlights, and after that, I'll start my discussion with the moon and the planets.

| December 12 | Venus and the crescent moon over the sunrise. |

| December 13 | Geminid Meteor Shower (and new moon) |

| December 14 | Solar Eclipse (in South America) |

| December 21 | Solstice and Great Conjunction (and Ursids) |

The Wanderings of the Moon

If you've been following along for the last couple of months, you will be familiar with Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn in the evening skies. Jupiter and Saturn are the two brightest “stars” in the southwest after sunset, and Mars is the reddish “star” high in the southeast. Mercury and Venus used to be up over the sunrise. Perhaps you also watched the moon pass by all of the planets in turn as it circled around the “planet highway”, i.e. the zodiac. This month, Mercury is nowhere to be found. It sank into the sunrise and will be too close to the sun to be seen all month. Look for it to reappear over the sunset in another month. Venus is sinking after Mercury into the sunrise, and Mars has lost the luster of opposition, but all of the planets other than Mercury can still be found in roughly the same places they have been keeping, and will continue to be there for much of the month. And the moon will step through another series of conjunctions this month as it again orbits past each of them in turn.

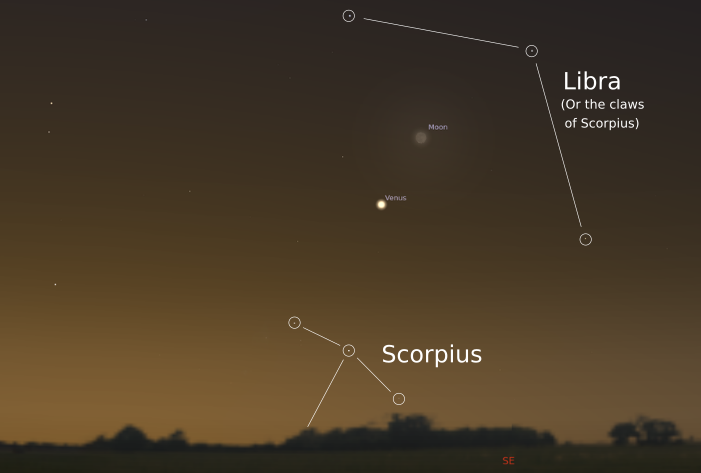

The moon was full over a week ago, at the time of the eclipse. It has now passed last quarter, and is waning in the morning skies as it closes in on the sun. If you have clear views of the eastern horizon, the pre-dawn skies should be quite pretty all weekend. The morning of Saturday the 12th should be especially lovely, with a thin crescent moon hovering just over Venus over the sunrise. By Sunday the 13th, the moon will probably be too low and too dim to be visible in the glow of sunrise, but you may catch it if you have good timing, good eyesight, and a clear eastern horizon. Maybe you can also catch the first few stars of Scorpius emerging just ahead of the sun, as the sun passes from Scorpius into Sagittarius, allowing the Scorpion to climb out of the sunrise.

After passing Venus, the moon will pass the sun on Monday, December 14, becoming new again. When a full moon is aiming well enough to hit the earth's shadow in the sky and cause a lunar eclipse, as it did during the last full moon, then it is usually still aiming pretty well two weeks later, and it will hit the sun in the sky at the time of the next new moon, causing a solar eclipse. Solar eclipses and lunar eclipses usually occur in pairs (and occasionally triples), two weeks apart, at successive new and full moons. At the last full moon, we had the chance to observe a (penumbral, unfortunately) lunar eclipse. At the coming new moon, on Monday, December 14, there will be a solar eclipse. And you will be lucky enough to see it if you live in Los Angeles...Chile.

Many residents of South America will be treated to a partial solar eclipse, and will be able to see the sun partially blocked by the moon. However, as you may know, a total solar eclipse, in which the sun is blocked completely and day turns temporarily to night, is only visible to observers standing along a narrow “path of totality”, roughly 70 miles wide depending on circumstances. As close as I can tell, the path of totality for the upcoming solar eclipse will miss all major cities, and will make landfall only along a narrow strip of rural Chile and Argentina. Conceptión and Los Ángeles, Chile are the closest cities I can find. (For maps, schedules, and animations, I like Time and Date's web page. If you'd like to watch the event without voyaging to the southern hemisphere, they will also broadcast a live stream of the eclipse as it happens, with partial eclipse beginning at 7:34 AM Central Time, or 5:34 AM Pacific Time, and peak eclipse occurring at 10:13 AM Central Time, or 8:13 AM Pacific Time, on Monday.)

After passing Venus on the 12th and the sun on the 14th, the moon will reappear in the evenings over the sunsets, and begin the “waxing” half of its cycle. It will proceed to pass by all of the evening planets as it grows and crosses the evening sky, heading towards opposition and fullness again. It will pass Jupiter and Saturn next Wednesday and Thursday the 16th and 17th, and Mars on the 23rd, and finally become full again on December 29th, one month after the penumbral eclipse. This time, it will just be a normal full moon.

The Solstice and the Great Conjunction

In the evening skies, while they wait for the moon to pass them, Saturn and Jupiter have also been creeping gradually towards the sunset, as the sun catches up to them along the zodiac. They have also been gradually drawing closer together, as if they were heading towards a rendezvous with each other. Will we get to see these two side-by-side before we lose them into the sunset...?

Jupiter and Saturn are the two slowest “wandering stars”. Saturn is the slowest, and this was probably the origin of the name—the Roman deity Saturn evolved from Chronos, the Greek god of time and the namesake of all chronicles and chronologies. In the sky, Jupiter slowly advances on Saturn as they both march slowly around the zodiac, and every 20 years, Jupiter laps Saturn. Every 20 years (19.86 years on average) Jupiter passes alongside Saturn on the highway of planets. The last time this happened was May 28, 2000, and here it is 20 years later. Jupiter will indeed pass Saturn this year, on December 21. They will be near the sun at the time, but most people should still be able to briefly observe this “Great Conjunction” low over the sunset.

There are a couple of things that make this conjunction extra special...even historic. For one thing, December 21 is (coincidentally) the day of the winter solstice. On December 21, the sun will reach its most southerly station over the Tropic of Capricorn. Like a pendulum stopping at the top of its swing, the sun will stop its southerly migration over the Tropic of Capricorn, stand still momentarily, and then turn around and begin its northerly return towards the Tropic of Cancer. On this day of stationary sun, the southern hemisphere will have the longest day of the year, and the northern hemisphere will have the longest night. And this year, Jupiter will almost touch Saturn on this same day of solar standstill, or “sol-stice”.

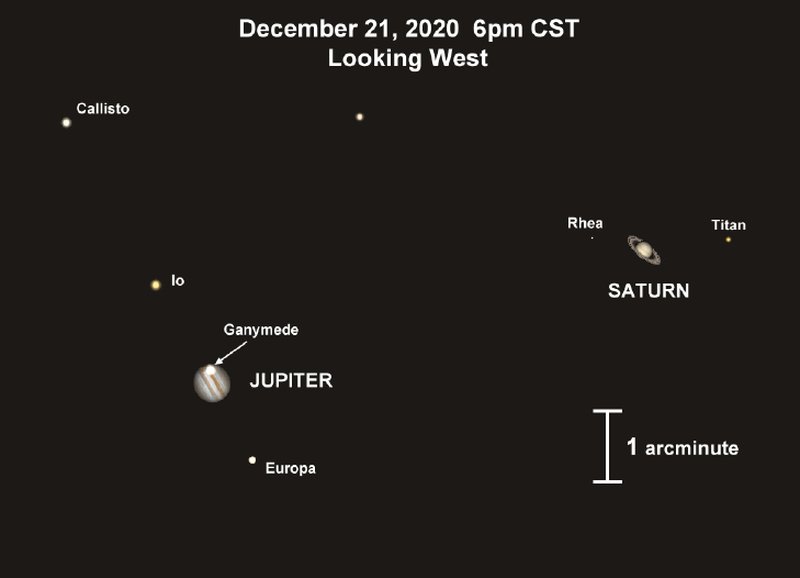

Secondly, and much more importantly, is how far apart the two planets will appear in the sky. In some conjunction years, Jupiter passes closer to Saturn in the sky, and sometimes it stays farther away. The closest approach distance varies quite a lot from one conjunction to the next, but we can take about 1° in the sky as a rough average. That's two moon widths, or about the width of your pinky finger at arm's length. This year, Jupiter will approach Saturn to a tenth of that distance: about 0.1°. That's one-fifth the width of the moon, or roughly the width of a paperclip held at arm's length! For a few people, depending on the quality of your eyesight and your weather, the two planets might be so close that you can't tell them apart. They might be so close that they look like a single star! In the 3000-year period from 0-3000 A.D., only 7 other conjunctions were (or will be) closer than this. And some of those were too close to the sun to be seen. The last time Jupiter and Saturn were this close was in 1623, but they were too close to the sun to be seen at that time, and the last time earth-dwellers could actually observe such a close conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn...was the year 1226, when Roger Bacon was 6 years old, and Galileo's invention of the telescope was still over 300 years away.

So this is definitely worth some effort to observe.

The best day will be solstice day, Monday the 21st of December. If you compare that day with a day before or after, you may notice the difference, especially if you hold up a pen or something, or if you have something in the distance with which you can compare and measure distances in the sky. But remember that both Jupiter and Saturn are slow movers. From December 17th to Christmas Day they will still be closer together than a moon's width, and that is still much closer than the majority of conjunctions. So if you want to see them at their closest, aim for the sunset of the 21st, but don't despair if you have foul weather on that particular day. This will be an on-going event.

For most U.S. viewers, the planets will start to be visible roughly a half hour after sunset and will stay visible for roughly an hour. That means roughly 5-6 PM in most places. If you go out before this, the sky will still be too bright, and will drown out the planets, especially fainter Saturn. If you go out after this, Jupiter and Saturn will have sunk too low, and will have set below the horizon, or will be lost in the haze close to the horizon. However, this time window will vary depending on your latitude and time zone, and could be considerably narrower than an hour, especially if you live far from the equator. Those who live above roughly latitude 50°N could have a very hard time picking the planets out of the sunset before the planets set themselves. So you may want to start your observations well before the 21st. You may want to scout some locations with clear horizons, and confirm your exact time window, before the big day itself. Water to your west would be ideal. If you live on the West Coast, I suggest the beach.

If you have binoculars, definitely take them with you. If you have a backyard telescope, or if you can find a local astronomy club with a planet-watching event, consider viewing the event through a telescope. This conjunction will be so close, you should be able to fit both Jupiter and Saturn into the same field of view! You could see Saturn's rings and Jupiter's moons all in the same telescope at the same time!

(Credit P. Hartigan. Adapted from Stellarium)

If I were presenting this material to children, I could anticipate a few questions:

Do Jupiter and Saturn ever actually collide in the sky? No...at least not in recorded history, nor in the foreseeable future. Predictions become more difficult and less accurate the farther you go forward in time or back into pre-history, but pretty good calculations can be made for several thousands of years. And by such calculations, the last time Jupiter eclipsed Saturn was 6856 B.C., and the next time it will happen will be 7541 A.D. In the latter case, if the calculation is accurate, the eclipse will be total and if you could look at it through a telescope, you would see only the tips of Saturn's rings showing from behind the disk of Jupiter.

When will the next one be? The next two conjunctions, in 2040 and 2060, will both be more than 1° apart. However, they can be interesting for different reasons. The next one in 2040 will occur near the bright star Spica. Jupiter, Saturn, and Spica will form a nifty little triangle, with the moon right in the middle. And if you are very young, maybe you will live to 2080, and have a chance to see another historic conjunction. The one on March 15, 2080 will be as close as—actually just a hair closer than—the one this year, and it will occur farther from the sun in the sky, so you can wait until long after sunset, and look higher in the sky, where the viewing will be much better.

For a more comprehensive analysis of the upcoming Great Conjunction, you might find this page by an astronomy professor to be helpful.

The Geminids and the Ursids

In addition to the antics of the moon and the planets, there are two annual meteor showers coming up soon: The Geminids, which peak this weekend on the night of the 13th-14th, and the Ursids, which peak on the night of the 21st-22nd.

Unless you are an avid meteor watcher, you can probably neglect the Ursids and not miss much. The average rate at the peak is only around 5-10 meteors per hour, with occasional bursts of maybe 25 per hour, and the peak is very brief, lasting only a single night. Compared to the Geminids, which are longer lasting, have much higher rates, and peak only a week earlier, this is pretty underwhelming. Considering the winter weather which can also befall the land around this time of year, it isn't too surprising that the Ursids are not a very popular meteor shower. One interesting thing about this year's Ursid shower, if you noticed, is that it falls on the same night as the winter solstice and the Great Conjunction. This year, we will have a solar standstill, falling stars, and a clash of planets all on the same day.

In stark contrast to the Ursids, the Geminids have been described as “very reliable”, “always a highlight of the meteor year”, and “one of the brightest and richest” of the annual meteor showers. If you are going to budget your annual meteor-watching time, you should definitely put the Geminids near the top of your priority list. The estimates I've read vary, but I'd say that in clear dark skies, you will probably see 50-60 per hour, with the possibility of up to 150 per hour. And this year the Geminids coincide with the new moon (December 14th) and darker skies, so maybe you can optimistically expect numbers towards the higher end of that range.

What kind of meteors will they be? Meteors can be fast or slow, bright or dim, white or flame-colored. They can look like simple moving stars, or they can leave persistent trails behind, or expand into fireballs. People who write reports on the internet often get their information from each other, and they don't always check the ultimate sources, so the information out there is a little inconsistent. (One account I read described them as “bright, white, and slow”, another as “bright, fast, and yellow”.) And meteor showers by their nature tend to be somewhat erratic and unpredictable anyway. By most authoritative sources, Geminid meteors tend to be bright and bold, but they don't tend to leave “persistent trains” or explode into fireballs. According to the American Meteor Society: “The Geminids are often bright and intensely colored. Due to their medium-slow velocity, persistent trains are not usually seen.” Being slow may mean that there are no trails of fire, but it also means that you have more time to look around when your friend yells “meteor!”, and some extra time to enjoy the sight once you find it. Watching for fast meteors can be a little like a game of whack-a-mole, while slower meteors give you more time to enjoy the show. So with the Geminids, I think you can reasonably expect to be impressed by numerous bright fly-bys. If you want fireballs or flaming tails, you may be disappointed, but by all other measures, this should be a great show.

When you do see a meteor, can you tell if it belongs to the Geminids? Or it is just a normal background “sporadic” meteor? What's the difference? Follow the meteor trail backwards to see where it came from. If you do this for several meteors during a shower, you will discover something interesting about the meteors of a shower. They are not random, but organized. If you watch for meteors on any normal, non-shower night, you might see one or two per hour, but they won't be organized. They will come from random places and head in random directions, like swarming insects. The meteors of an annual “shower” all come from the same place among the stars. They all fly outwards from the same constellation. They “radiate” from the same point in the sky. It's as if there is a cloud of debris out there in space, and the cloud is flying past us (or we are flying through the cloud), and the particles of the cloud are making streaks through space as they pass all around us. And the radiant point shows the direction the cloud is coming from (or the direction we are flying towards).

Each of the various annual meteor showers has its own special constellation that the meteors fly out of, and this gives a good way to name each shower. The “radiant point” of the mid-December shower lies in Gemini, hence the name “Geminids”. Actually, the radiant almost coincides with the star Castor, one of the two “twins” in mythology, and one of the two brightest stars in the constellation. (If you'd like a map of the constellation, Wikipedia has one, and you can also find it in my own Orion and Friends and Winter Hexagon worksheets.) Meteor showers tend to begin around the time the radiant rises in the east, and reach their strongest showing when the radiant is high in the sky. For the Geminids, this means very roughly 7 PM and 2 AM, respectively.

So, when do you go out, and where do you look? If you want to observe this shower, like any shower, don't expect to wander outside, see a few meteors, then wander back inside. Actually, given how bright and frequent Geminids are, you may see a meteor or two that way. But to really appreciate the show, you need to find a dark location with a broad view of the sky, then settle in, give your eyes a chance to adjust to the dark, and enjoy the show for at least a half-hour, if not a couple of hours. So prepare to keep yourself comfortable for awhile outdoors on a December night—Dress warmly, and bring a sleeping bag, blankets, lawn chairs, and some hot cocoa if you have to. On the plus side, among its other great features, the Geminids start unusually early. Many meteor showers are visible only before dawn, but the Geminids put in a decent showing even before midnight. You may see some as early as 9 or 10 PM, although the best time should be around 2AM.

Furthermore, the Geminids have an unusually broad peak. Some meteor showers happen in a sharp, brief flurry of activity, only a few hours long, and if you miss it, you miss it. In contrast, the Geminids slowly build over many days, and then have a broad 24-hour peak, although they do fall off fairly sharply after the peak. The peak of the upcoming Geminid shower is predicted to be this weekend, on the evening of Sunday the 13th and the morning of Monday the 14th, but there is a good chance that there will be good displays all weekend long. If you have the time or interest, try going out Friday and/or Saturday night as well as Sunday.

Where should you look? Higher is better than lower, because the sky is clearest overhead, and rather hazy and wrinkly near the horizon. Looking around the radiant is better than looking directly at the radiant, or looking far away from it, because that's where the streaks will appear longest and brightest. In this case, your best bet is probably to face south, and let your eyes roam over the high southern skies. If you are out earlier, when Gemini is still rising, you may want to turn more southeast-ish.

For more information and some meteor-watching tips, you might like EarthSky's Page.

One final point of interest: Curiously, there are no reports of mid-December meteor showers more than about 200 years ago. The first reports of a mid-December meteor shower radiating from Gemini appeared in the 1800s, with rates of only 10-20 per hour. The Geminid show has been strengthening ever since. I wonder what it will be like in another few decades?

Happy Viewing!John