A Fading Moon and the Autumn Star

November 24, 2020

As November ends, the brilliant summer constellations of Scorpius and Sagittarius are all but gone from the evening skies, having sunk below the western horizon into the sunset. However, they are being replaced on the opposite side by the brilliant winter constellations surrounding Orion, just starting to rise above the eastern horizon. And in between, spread across the majestic dome of the November evening sky, is a raft of medium constellations, all united by a common story. Between Sagittarius touching the western horizon, and Orion touching the eastern horizon, is a sky full of characters from an ancient Greek epic.

The Andromeda Story deserves a discussion to itself, so I'll save that for a soon-to-follow issue. Today, I want to discuss some stellar markers of autumn, and an unusual full moon that we will have this month.

The Fading Moon

The full moon this month will occur in the wee hours of the morning on Monday, November 30, at about 3:40 AM (Central Time). If you go outdoors at about that time, and look closely, you may just notice something a little odd. It might seem ever so slightly faded on one side. If look two hours before or two hours after, you will just see a normal, bright full moon. And even if you watch all night you will never see any shapes or dark patches. It's almost a normal full moon night, except for a slight fading along one edge, so slight you might not even notice it. It's as if something whispy, some kind of thin misty shade, brushes past the edge of the moon, just as the moon passes the time of the full moon.

You may remember from the recent opposition of Mars that “opposition” means being on the opposite side of the sky, and on the opposite side of the earth, from the sun. The moon passes through opposition once a month, and becomes full every time it does so. But...the opposite side of the earth from the sun...isn't that where the earth's shadow should be? Why is the moon full instead of dark? Maybe the shadow is too small, and the moon doesn't aim very well, and the moon misses the shadow?

Astronomers as far back as ancient Greece could measure the positions of the sun and moon in the sky fairly precisely, and they discovered that this is the case. Every month, the moon passes pretty close to opposition, but not exactly through opposition. Although sometimes it aims better than at other times. Most months, it misses the place where the shadow should be, and we see a normal full moon. But once in awhile, it has better aim, it passes exactly through opposition, and we observe...a lunar eclipse.

And in some rare months, the moon aims better than usual, but still not well enough to hit the shadow. Sometimes it grazes by the edge of the shadow, coming close, but not close enough to actually touch the shadow. At these times, we may or may not observe a slight fading on the closer side of the moon. Why?

Have you ever observed that sometimes shadows have sharp edges, and sometimes they don't? If the light source is very small and bright, and the shadow doesn't travel too far through space before landing on something, then the shadow has sharp, crisp edges. But if the light source is spread out, and if the shadow has to travel a long distance before landing on something, then the shadow has fuzzy edges. The sun has a certain width to it, even seen from as far away as the earth. If it didn't, it would look like a star instead of a circle in the sky. And the earth's shadow also has a long distance to go before landing on the moon. So the earth's shadow must have at least a little fuzzy edge to it.

Astronomers call the “true” shadow, the dark center of the earth's shadow, the umbra, from the latin word for shadow. (The word umbrella is the diminutive of umbra. An umbrella makes a little shadow.) If you flew out into space, and into the earth's umbra, and looked back at the sun, you wouldn't see any of it. It would be entirely blocked by the earth. The fuzzy region of partial shade at the edges of the earth's shadow is called the penumbra. If you flew out into space into the penumbra, and looked back at the sun, part of it would be blocked by the earth, but you'd still be in sunshine, because part of the sun's circle would still be showing around the edge of the earth. This is what happens to the moon when it passes through the penumbra. It is still in the sunshine, but not as much of it as usual. When this happens, we call it a penumbral eclipse.

This coming Monday, at 3:40 in the morning (Central Time), there will be a penumbral lunar eclipse.

I generally didn't make a big deal about penumbral eclipses when I taught astronomy, because they aren't that dramatic and you can't learn much by watching them. With “normal” lunar eclipses, you get to see the distinct curved edges of the earth, and beautiful sunset colors playing across the face of the moon. During a penumbral eclipse, it just fades a little. Depending on how deep the moon goes into the penumbra, sometimes you can't tell any difference at all from a normal full moon. But if you want to search for the faded edge of the moon, and imagine the earth's shadow just beyond the faded edge, this Monday at 3:40 in the morning is the time to do it.

The actual start time is listed as November 30, 2020 at 07:32:22 UTC, or 1:32 AM Central Time, and the duration is given as 4 hours, 21 minutes. But the “beginning” and “end” of a penumbral eclipse only have meaning to astronomers. You probably won't notice any difference at all except within an hour of “maximum eclipse”, if even then. For the best chance of seeing a faded edge, I suggest going out within a half-hour of 3:40 AM.

Whenever there is a lunar eclipse, it is a good warning to keep your eyes open for solar eclipses...because they tend to occur in pairs. If you see a lunar eclipse during this month's full moon, you should keep watch for a solar eclipse at the time of the next new moon, two weeks later.

For those of us in North America, I have some good news and some bad news. The penumbral lunar eclipse will be high in the sky in the middle of the night for us, so we get to see it. And there will in fact be a solar eclipse in two weeks. But we won't get to see it. In fact, nobody in the world will get to see it, except for those living in a narrow swath of land crossing rural Chile and Argentina.

The Autumn Star

If you don't feel like getting up in the cold and dark of the pre-dawn hours to look for a slightly faded full moon, you could just go out in the evening after sunset, and check your bearings in the celestium. There are some stellar markers of autumn to look for, and you can keep tabs on what the planets are up to.

Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are all roughly in the same positions they have held for the last month. Mars has dimmed considerably as it fades into the distance following opposition, but it is still in roughly the same place in the sky, and it is still as bright as Sirius, the brightest star in the sky (which will also be rising in the late evening, roughly two hours after Orion). Jupiter and Saturn are still there, creeping along very slowly. If you've been keeping your eyes on these two, you might have noticed that they are gradually drawing closer to the sunset, following Sagittarius into the sunset. You might also have noticed that they are gradually drawing closer to each other. Will they cross paths soon? Will we get to see them together before we lose them into the sunset?

The moon is on its journey from west to east, passing the planets one by one as it grows in phase and heads towards its rendezvous with the earth's shadow. Tomorrow, on Wednesday the 25th, it will pass quite close to Mars—about 10 moon-widths, or roughly the width of three fingers held at arm's length.

Sometimes certain stars can serve as useful direction markers, giving you an orientation to your horizon and your sky, if you can recognize them. The North Star is the most familiar and most useful, because it never moves. It is always there, marking north. But there are others. In the late autumn evening skies, there is a bright star hovering low over the southern horizon, and reaching its peak in the early evenings. This star is Fomalhaut.

Fomalhaut can be hard to recognize by its constellation, because it doesn't have one. Well...it does have an official constellation, but all the other stars nearby are quite dim, which makes Piscis Austrinus, the southern fish, a pretty hard to find and unremarkable constellation. (Its more northerly brother Pisces is larger, but also quite dim, without even a bright star like Fomalhaut.) However, if you already know which way is south, you can usually recognize Fomalhaut simply as the brightest star over the southern horizon in autumn evenings. There aren't any other bright or even medium stars nearby.

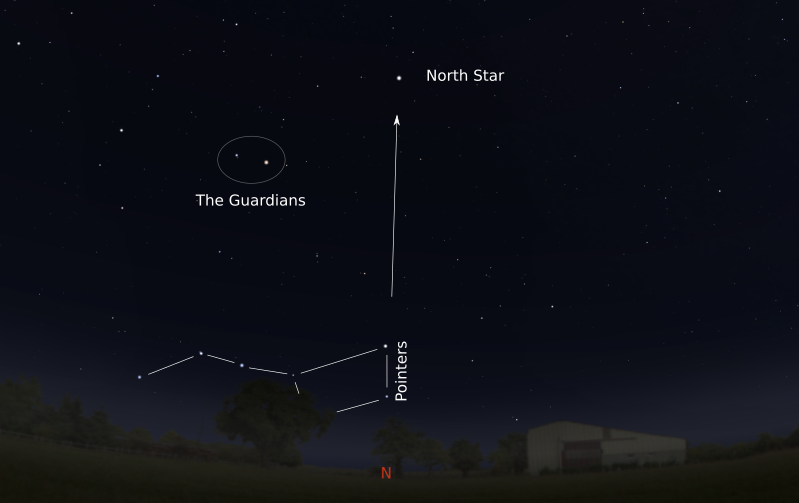

Thus on autumn evenings, the sky is marked at opposite ends by the North Star in the north, and this “autumn star” in the south. When any star in the south reaches the peak of its arc across the sky, and lies due south, like the sun at noon, we say it is “southing”, or that it has reached its “culmination”. At about the same time that Fomalhaut is southing (roughly 7 PM these days), Orion is just starting to rise in the east, and it will fully clear the horizon roughly an hour and a half later. At the same time, the two “Pointers” in the bowl of the Big Dipper stand due north, pointing straight up at the north star. If you have a clear view of the northern horizon, try to find these two stars at the end of the bowl of the Big Dipper, draw the line straight up to Polaris, then keep going through the top of the sky (the “zenith”), and back down to Fomalhaut. That line is your meridian, the North-South line crossing the center of your sky and dividing it into east and west halves. And around 7 PM these days, it will be nicely marked by the Pointers, the North Star, and Fomalhaut.