Experiments With Afterimages

Learn something about your retinas by staring at things.

Everyone has noticed that you see spots for a while after you look at bright lights. Some people may even have noticed that if you stare at the same thing for some time, and then look away at an empty wall or blank screen of some kind, you see a brief “afterimage” of the thing you had been looking at. But not many people have bothered to experiment with this phenomena. If you do this with your students, you can generate a lot of amazement, and perhaps teach them something about their retinas.

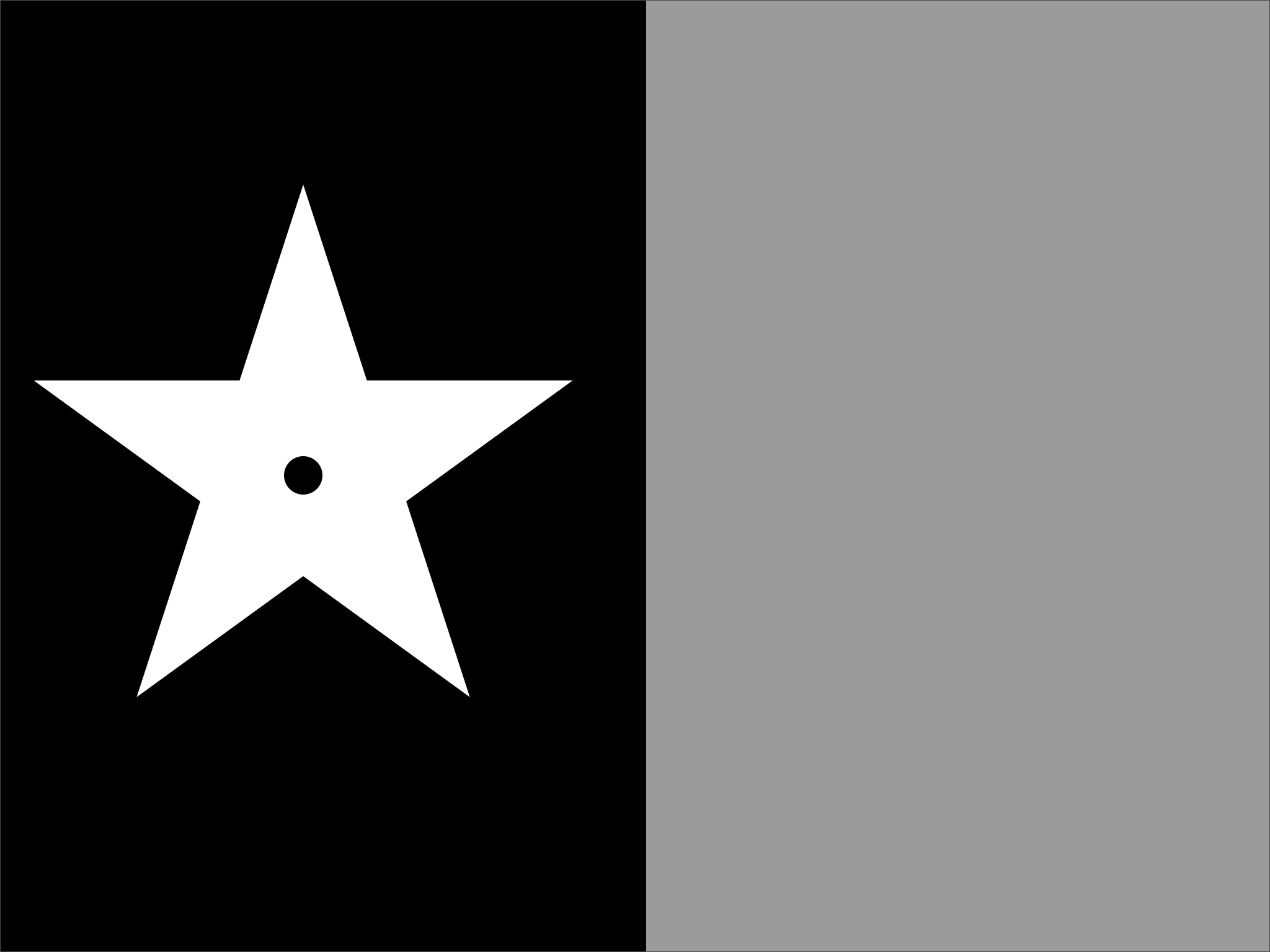

Simple Shapes in Black and White

Let's start with some basic bright-versus-dark experiments, using simple shapes. In the following picture, I have created a white star on a black background, with a gray area nearby. I put a circle in the center of the star simply to give you something small to stare at and to help fix your gaze at a single spot. In retrospect, maybe cross-hairs would have been better. Anyway, let's create a basic afterimage by staring at the center of the star, then looking away to someplace empty, either the gray area, or the white margin of your screen, or a white piece of paper. When staring, bear in mind that the more your eye wanders, the less distinct the afterimage will be. Students will often ask if blinking is ok, and the answer is yes, as long as you don't move your eyes. You can close one eye, or keep both eyes open. How long do you need to stare? That will depend on circumstances and how vivid you want the afterimage to be — ten seconds is usually enough, but twenty will produce a better afterimage.

Now, what do you notice when you see the afterimage? Afterimages can be much more than just the “spots” that you see after looking at a bright light. They can actually have shape. They can actually be an image...of something that isn't there. You see an image of something you used to be looking at, even after you stop looking at it. You will also notice that the image is inverted. If you were looking at a white star on a black background, the afterimage will be a black star on a white background. But how can you see a black star on a white background if you look at something other than a white background? Try the gray background and it should still look like a white star on a gray background. But what if you were to look at a black background? Would you still see the afterimage?

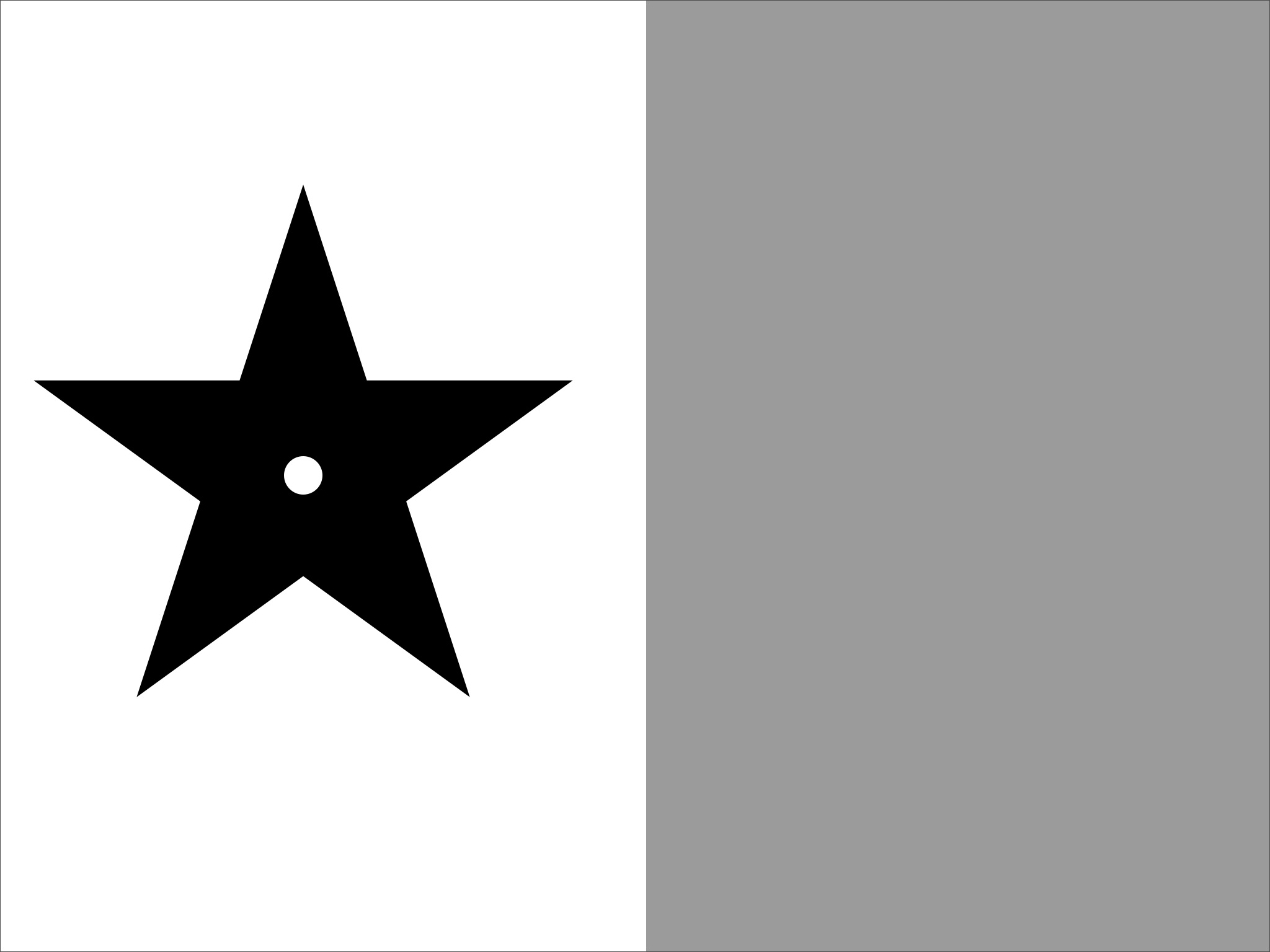

After staring at the white star above, you could just try shifting your gaze a little, but stay on the black background. You might notice that the afterimage is still a black star on a white background, or more precisely a darker star against a lighter background. Relative contrast seems to be the important thing. Let's test this some more by trying the reverse problem. In the figure below, I have a black star on a white background. If you stare at this one, and then look at the gray area, you will see white on gray as expected, but what if you look at a white background after staring? How can you see a white star on a white background?

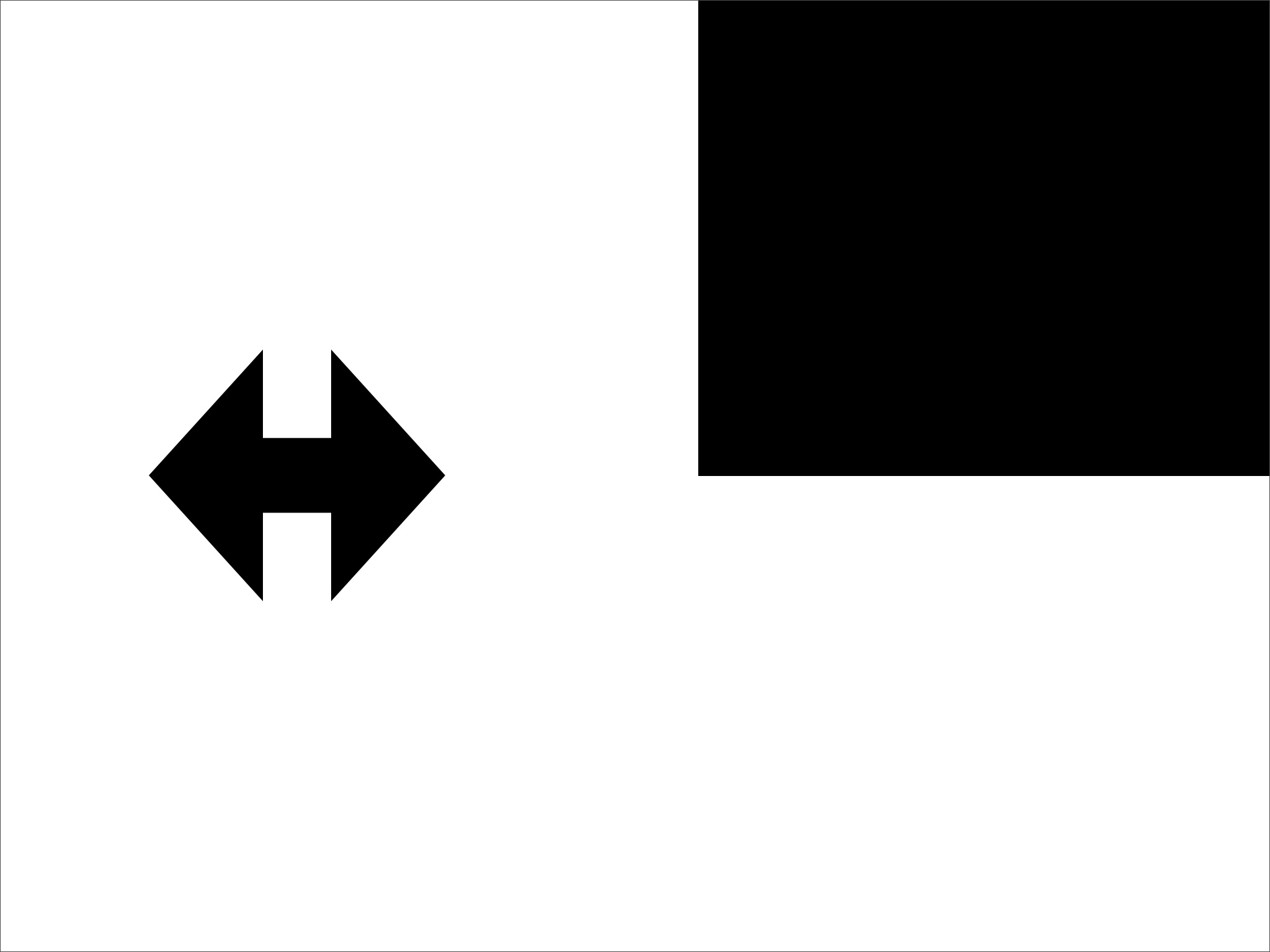

Again, you will notice that wherever you look after staring, the parts that were relatively dark in the original image will be relatively bright in the afterimage and vice versa. This next image has both black and white blank areas for comparison. Whichever one you look at, the afterimage is always the opposite of a black arrow on a white background; it is always a brighter arrow on a darker background.

Afterimages are all about difference. Like sensation generally, we often notice changes more vividly than we notice pure, static, stimuli, especially if we have “gotten used to” a dull, constant stimulus. The skin on the outside of your body lets you know whenever something else comes into contact with you. It gives you sensations of pressure, warmth, cold, and provides you with information about what's touching your body. But if something touches your body for a long time (the cold water of a swimming pool, the pressure of your clothing), you get used to it, and maybe you stop being aware of it altogether. Then when you get out of the pool or change your clothes, you become aware of it again. Your retinas seem to work in a similar way.

If you've performed the eyeball dissection, you will have observed the retina — that pink skin at the back of the eyeball. Your eyeball is constructed to make an image “land on” or “touch” this pink retinal skin at the back, which then somehow “feels” or senses the image. But staring at the same thing is like having the same thing touch your outer skin. Unless it is too strong or painful, you get used to it and the sensations become more or less dulled, and then you notice the change when you look elsewhere. If you stare at a black-and-white shape, the parts of your retina that received the white part of the image get used to white, and then tend to see anything darker as black by comparison, and the parts of your retina that received the black part of the image get used to black, and when you look away, they see everything as brighter by comparison. You perceive a brightening as relatively white, and a darkening as relatively black.

Afterimages in Color

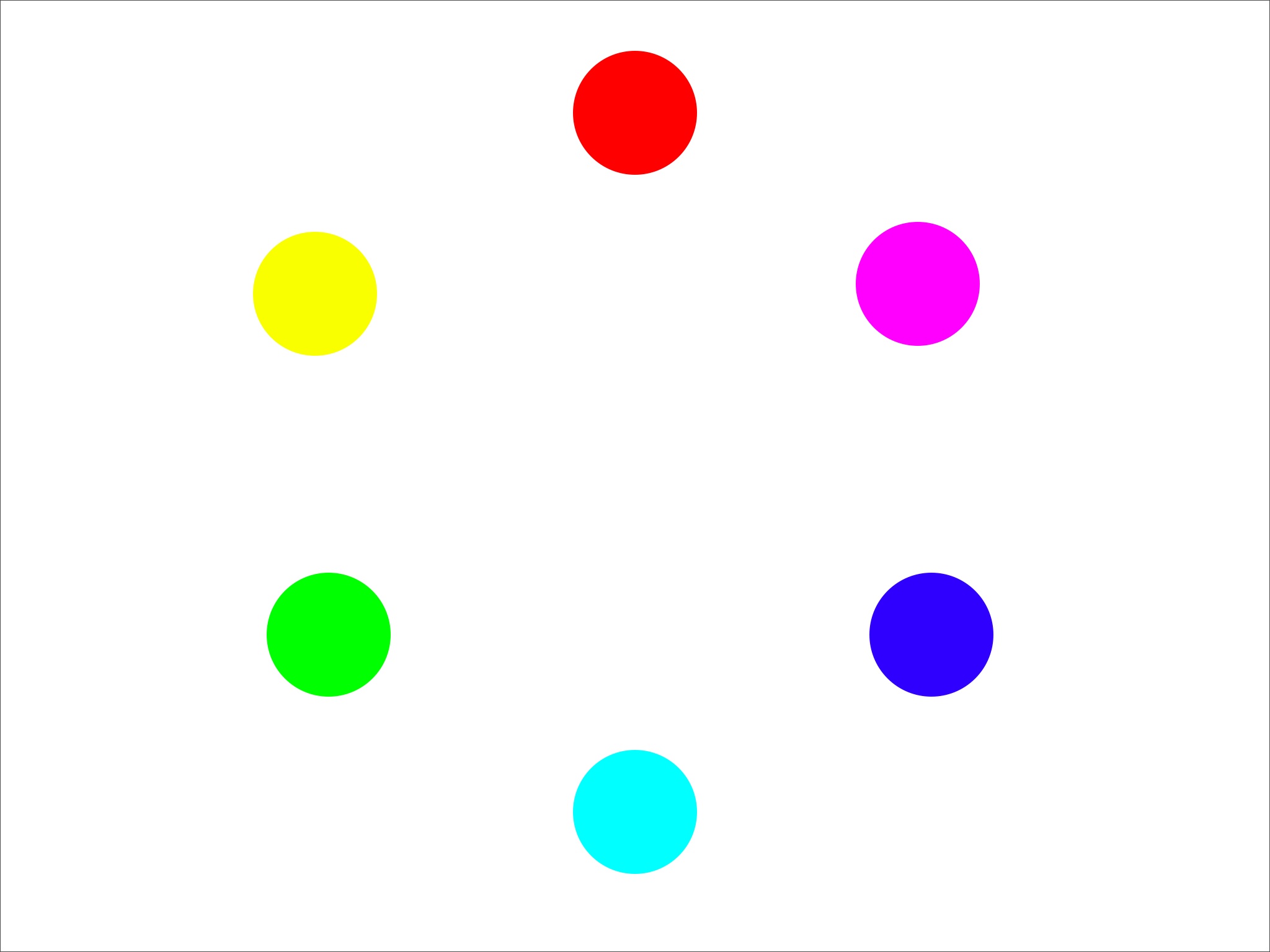

Now for the fun stuff. We see in color — can we see afterimages in color, too? What kind of afterimages do you see after you stare at colors? Try staring at the center of one of the colored circles, then shifting your gaze to the white area in the center of the page. What can you observe? Try all the circles and see what happens. (By the way, as you're staring, you may notice yourself becoming less aware of some of the other circles in your peripheral vision. This is your eye “getting worn out” or “getting used to” what it's looking at.)

You can see afterimages in colors, but there's something funny about the colors. Each color has its own “opposite color”. The afterimage of red is cyan, and the afterimage of cyan is red. All colors come in pairs, each of which is the afterimage color of the other. We call these complementary colors.

Why in the world would we see color in this way? Well, there's a full modern answer, having to do with rods and cones and color theory, but maybe we can work out a much simpler, if cruder, answer. Think about your retina as a patch of skin. “Feeling” bright and dark would be relatively simple. Your retina could do that in the same way your skin feels more or less pressure, or hotter or colder temperatures. But “feeling” color is more sophisticated. The sensitive skin of your retina must have a spectrum or a variety of “responders” to sense the variety of colors in the world. So when you stare at colorful scenes, some of these responders are getting tired, and some aren't. Whenever you stare at certain colors, certain parts of your retina are getting worn out, and the rest are remaining fresh. The remainder of your retina, the parts that are not getting worn out, must be the parts that are responsible for seeing the opposite color. Opposite or complementary colors must trigger opposite or complementary portions of your retina's color palette.

Can we have some fun with colorful afterimages? Suppose we want to color a flag in complementary colors, so that we can stare at it, then look away and see an afterimage in the proper colors? We'll need to know the proper “opposite” colors to use. For red, white, and blue flags, the opposites will by cyan, black, and yellow. (Light blue is much more common than cyan in typical small crayon or colored-pencil boxes, and it is close enough to cyan for these purposes.) If you click on the American flag below, you can download a file with a normal US flag, a US flag in complementary colors, and a blank US flag for students to color. I have made the flags about half-page size, and left the bottom of the pages blank. I found that this worked well with my students — the flags were not so large that they took forever to color, and the blank space at the bottom gave them a blank space to look at when they wanted to see afterimages. If you have students color their own flags for the purpose of making afterimages, you may want to remind them that the more thorough and the more vivid the coloring, the more vivid the afterimage will be.

Alongside the US flag, I have also prepared similar files for the United Kingdom, South Korea, and South Africa. These are all flags that are complex enough to make interesting afterimages, but still relatively easy for me to draw.

Many European countries have easy-to-draw Tri-Color or Nordic Cross flags, and for whatever it's worth, I made similar files for all of these. If you live in one of the following countries, and you want your children to color your national flag in either true colors or complementary colors, help yourself to these files: