The Compass Rose and the Horizon Calendar

Notice the symmetry in the sky, record it in the ground in an artistic design, and use this framework of directions to name every direction around you.

Go outdoors and look at the horizon around you. Your view of it will be different in different locations, and will be more or less cluttered in different directions, but on the open ocean it would be a perfect circle surrounding you — a perfect horizontal circle. (Etymologically, I'm not sure which word came first — horizon or horizontal. But they obviously developed together.) And regardless of what your view actually looks like from any specific location, we can use this perfect imaginary circle as a useful marker and reference for all global and celestial measurements. We idealize the ground as a horizontal plane and the sky as a hemispherical dome, and the horizon is the circle where the two meet.

How can we give names to all the different positions on that horizontal circle around us? How can we give names to which way we are looking or pointing? Perhaps one of the first activities that elementary students should perform in Astronomy or Earth Science is to become familiar with how we name terrestrial and celestial directions. We start by naming certain special directions on the horizon (the cardinal directions), and then we can get more refined from there.

Cardinal Directions

Certain special events always happen in the same direction, every day, no matter where you are. If you watch the sunrise for several days in a row, you will notice that the sun always rises in the same direction … on that side of the house, or over that hill, or wherever the sun rises from where you are. We name this special direction where the sun always rises “East” … from a word that can be traced back to Greek and Latin roots for “dawn.” Students should likewise notice that the sun goes down over there, in that direction, opposite to East, every day, no matter where you are. We name that special direction where the sun always sets “West,” which relates to the Latin vesper, or evening. In between morning and evening, the sun goes high in the sky, but if you pay close attention (and assuming you do not live near the equator) you find that it does not ever go directly overhead. You can prove this by tracking shadows through the course of a day. Vertical poles will never point straight at the sun, and their shadows will never vanish. Our name for the direction of the sun at mid-day (South) has roots that are a bit more obscure, but it is probably related to the word “sun.” The fourth of the “four corners of the horizon” is the direction opposite to the sun at mid-day, the direction that shadows will point at noon. There isn't anything particularly interesting in the sky in this direction … at least not during the day. If you wait until after the sun goes down, however, you can find one certain particular star, the one halfway between Cassiopeia and the Big Dipper, that is always there. (Again, I’m assuming you live in the Northern Hemisphere.) Most stars are in different places at different times, but this one never moves. It is always there, regardless of the time of night or the month of the year. This direction, of course, is “North,” and the star is Polaris, or the North Star. (I have been unable to determine the ultimate origin of the word “North.” It is probably as old as time.)

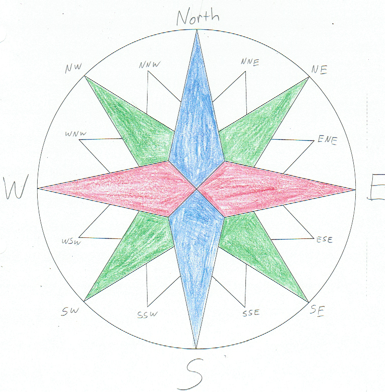

Once you give names to these four special “cardinal” directions given to us by the sky, what if you want to be more precise, and name a direction that isn’t exactly one of these four? What’s the direction of that boat over there, the one between East and South? One way is to just put together the directions on each side. We make a compound name from the two cardinal directions on either side. But should we say ‘eastsouth’ or ‘southeast’? Just so everybody does it the same way, we agree to always name North or South first, followed by East or West, and now we have names for four more intermediate directions: Northwest, Northeast, Southeast, and Southwest. But what if we want even more precision? What if there is something between North and Northwest, and we want to name that direction? Well, we can just do the same thing again, of course. We can compound the names a second time, and we can make eight more direction names this way. (This time we agree to always name the cardinal direction first: It's ’North-Northwest’, not ‘Northwest-North’. Also, we can say it either ‘North-Northwest’ or ‘North by Northwest’.)

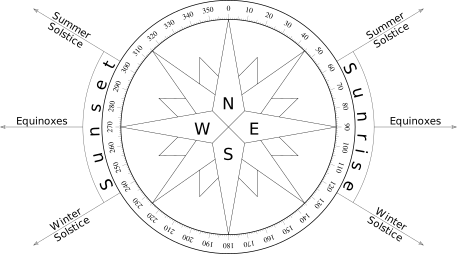

Now that we can name any direction we want, it might be useful if we drew on the ground a whole set of arrows pointing in all directions, showing the names for every way all in one pretty picture. If we do this, we have a Compass Rose, something like this:

The "Horizon Ruler"

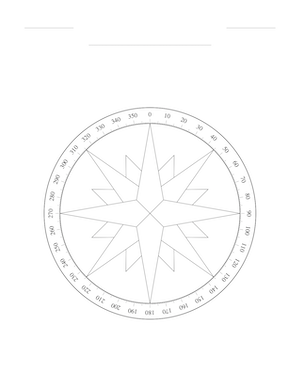

What if we want to keep going? What if we want to name the direction between Northeast and North-Northeast? I suppose we could keep using the same idea, and put together the names of the two directions on each side. But it starts to get silly. Did you say Northeast-North-Northeast, or Northeast-East-Northeast, or was that East-North-Eastnorth-Northeastnortheast.... Yuck. The idea of naming directions by combining cardinal direction names is great for rough, everyday orientation. But for precise measurements, we need something better. If we are sailing a boat or flying an airplane, and we need to be able to name any and all directions, conveniently and precisely, we need a number line, a “horizon ruler” of some kind.

Junior high students, or elementary students with some mathematical sophistication, may appreciate the method navigators use for this: we name the direction by saying the number of degrees clockwise from North. We effectively wrap a ruler around the horizon, starting from North, and counting degrees clockwise. In navigation, we measure the direction a boat's bow is pointing in the same way, and then we call this measurement the boat's “heading.” In astronomy, we measure the places on the horizon where things rise and set in this way, and we call this measurement the “astronomical azimuth.”

Solstice Marks

As you are probably aware, the sun doesn’t usually rise exactly due east and it doesn’t usually set exactly due west. If you pay close attention through the course of a year, you will notice that the sun's position on the horizon shifts back and forth in a rhythmic annual oscillation. (For a visual demonstration of this, you could try having students draw sketches of the sunrise or sunset from their house in different months of the year, or you could just show them a nice composite photograph.) Twice each year, at the midpoints of the oscillation, the sun rises due east and sets due west, and its daily circle through the sky is split into equal halves, giving us equal amounts of sunshine and night. We name these days of equal-night the equinoxes. And once each cycle, the sunrises and sunsets reach a northerly extreme, where they stop moving northward along the horizon, turn around, and go back in the other direction. We call this day when the sunrises and sunsets ‘stand still’ the solstice. There is a complementary southern solstice at the opposite end of the cycle. (If we were to establish a calendar for dividing the year into parts that we can name and count, these four events - the solstices and equinoxes - would be ideal division points for year parts. However, for historical reasons, our modern Gregorian calendar is not lined up with these four year markers, and the solstices and equinoxes now fall on irregular dates in the middles of our modern months. In the northern hemisphere, the spring equinox, summer solstice, fall equinox, and winter solstice fall very roughly on the 21st of March, June, September, and December. In the southern hemisphere, the same events happen on the same days, but we would reverse all the names, because the weather is backwards. Near the equator, where there is little or no difference between the seasons, we should probably just call those days the March equinox, June solstice, September equinox, and December solstice.)

In any case, one of the first steps towards scientific civilization occurred when primitive people constructed a sort of compass circle on the ground, and marked these four special days of the year with stones around the circle. Later on, royal observatories did the same thing, much more systematically and mathematically. What if we want to mark the seasonal sunrises and sunsets on our colored compass roses? What if we wanted to turn our paper compass roses into a sort of preliminary observatory? The equinox marks are a little superfluous; at the equinoxes, the sun just rises due east and due west. The solstice marks will vary with latitude, and in the menu below, you can find blank and labeled versions of compass roses with solstice marks for most latitudes. The preview image shows what it looks like at Latitude 40° North.

I haven't included any compass roses for latitudes inside the Arctic or Antarctic circles. Near the poles, you can't put solstice markers on your compass rose, because at the solstices near the poles, the sun never sets (or never rises), and stays above (or below) the horizon all day long.