Maps of the Moon

Simple "man-in-the-moon" doodle maps, and detailed feature maps, to help children recognize the face of the moon in the sky.

As a science teacher, I sometimes thought: “What's the point of teaching kids all this professional technical jargon? What use is this stuff to children?” So I tried to make the material simpler and more “relevant” … but then I ended up thinking: “Now it's childish and silly. The kids are going to be unchallenged and bored. They want to see things they haven't seen before, and learn things they didn't know before.”

This is one of the difficulties in being a good science teacher. I'm not going to say you have to find the right “balance” between simple and abstract stuff, because it isn't a matter of balance. It's a matter of progression. You have to start with things that kids can see and find interesting and relate to, but then you have to go somewhere with it. You have to show them how you can delve into obvious curiosities to reach hidden facts. One of the challenges of being a good science teacher is finding the right logical progression, by which you can climb from the obvious evidence to the abstract truths. You need to find a path of steps from the obvious to the hidden, from the simple to the fancy, from the base to the exalted. If you can do that, it becomes a fascinating journey.

Learning to recognize the face of the moon provides a nice example of this sequence.

The Rabbit in the Moon

If you ever have a chance to see the sun in the sky without the usual glare around it (perhaps through a pair of eclipse glasses, or through a thin layer of clouds), you may find that the simple beauty of the luminous disk is captivating. It's a perfect glowing circle in the sky. The moon is not like that. Besides having phases, the moon also has blotches and spots and freckles. The moon has a face.

Have you ever tried to make shapes out of the spots on the moon? Perhaps you have stared at the shifting clouds in a summer sky, and imagined ducks, or cars, or dragons. Have you ever tried to do the same thing with the freckles in the moon? We can start to befriend the moon simply by studying a full moon, and imagining what we see in the dark blotches. (And the value of doing this is very similar to the value of learning to recognize constellations. By finding memorable shapes, we begin to build a collection of useful landmarks.)

The downloadable handout below contains a picture of a full moon, with some suggestions for shapes that I used with my own students. (I have deliberately blurred the image a little, because I want to focus on shapes you can actually see in the moon in the sky. Getting a better look through telescopes can come later.)

Now, look at the face of the full moon and tell me what you see.

Children often see the series of puffy blobs on the right hand side as a poodle, or some other kind of puffy animal. I have heard that Asian cultures traditionally see it as a rabbit. Personally, I sometimes think of it as a lobster claw. The moon is most prominent in the convenient evening hours when it is near the first quarter of its phase cycle, at which point it is high in the sky with a dark left side. At these times, the blobs on the upper right, together with the dark patch in the center, look to me like the claw of a lobster reaching out from the dark side. (Sometimes I could persuade my students to agree with me about this, sometimes not.)

The darkness on the upper left side is quite round, but with a bump on one side, and a thin streak of darkness running along the outer edge, in front of the bump. I tried to tell my students that this was a face, perhaps Charlie Brown, reading a book or a newspaper. The bump is Charlie Brown's nose, and the streak is the newspaper. Several of my students tried to tell me that it was a diver, arcing sideways into a pool. The bump is the diver's ear, and the streak is an arm raised over the diver's head.

There is a curve of darkness in the middle of the moon that is smaller and harder to see in the sky, but it can be a useful marker for the center of the moon. I would draw the outline on my whiteboard, and many of my students would instantly recognize my outline as a Lego Hand.

The darkness on the lower left is a little more muddled in places, and it can be hard to agree exactly where to mark the boundaries between dark and light, and where to draw the edges of the figure. There is a fairly distinct circular area that can serve as a head, and then the darkness on both sides can be shoulders or wings. My students could generally see it as some kind of winged creature — bat, bird, angel, eagle, something like that.

I can make out almost all of these features in the face of the full moon in the sky. I used to be able to see the Lego Hand and the “newspaper” next to the head with effort, but my eyes aren't nearly as sharp as they used to be.

Official Names for the Features

Now that we have some practice at finding features in the face of the moon, it might be interesting to ask if the face ever changes. If we watch the moon at different times, in different parts of the sky, and in different phases, will the features change, like the clouds drifting across the summer sky, or will they stay the same? Or will they change but in a repeating way, like the phases?

A valuable classroom exercise might be to collect and examine as many photographs of the moon as possible. Will we be able to recognize the same features again? Will there be new freckles? I would show a series of such photos to my students and ask what they noticed, and it was always fun. (I hope to be able to offer a slideshow of such photos on this website one day, but first I need to obtain the rights to use the photos. If you are a photographer, I'd love to hear from you.)

The Moon's Secret

What we discovered was that, no matter the time of day, no matter the place in the sky, and no matter the phase of the moon, we always saw the same features in the face of the moon. Depending on where the moon is in the sky, the face might be rotated clockwise or counter-clockwise. If you live in the southern hemisphere the face will be upside-down (as compared to the “normal” full moon, such as the one I included in my handouts). And when the moon isn't full, some of the features might be hidden in the shade on the dark side. But we never see any new features. We always find the same shapes in the same arrangements. The front face of the moon is constant. Isn't that weird? If the moon is a sphere loose in space, wouldn't we expect it to turn, and show us different sides at different times? But it doesn't. However it moves through space around us, the moon is always careful to keep its face towards us, and to keep the mysterious far side forever hidden. It's as if the moon has a treasure or a secret on the other side, and it makes sure that we never get to see it.

(If you pay really close attention, you might notice that the moon does wobble slightly. Once in a while, you might notice that you can see a little farther around one side than you usually can, or that features near the edge are a little closer to the edge than usual. This slight wobble is called libration, and it means that, over time, earth-bound observers can see slightly more than one hemisphere of the moon.)

The Four Sides of the Moon

Why would the moon's face be rotated clockwise or counterclockwise? Is there any rhyme or reason to which way it is turned? And if it can be turned, then how do we know which way we should turn it when we draw it on paper and make a map? If the face can be rotated at different angles, then which side is the “top” and which side is the “bottom”?

There's another curious fact you might notice if you pay careful attention to all the pictures of the moon. Whever the moon is rising in the east, the “rabbit” side of the moon is pointing up. Whenever the moon is setting in the west, the “rabbit” side is pointing down. It's as if the “rabbit” side is the front of the moon, leading the way as the moon moves across the sky. And the opposite side, the one with the “head” and the “upside-down bird”, is the “rear” of the moon, following behind, and facing backwards at the place it came from. If we imagine an arrow through the face pointing which way the moon is moving through the sky, then the arrow always passes through the same features on the face. And this is true no matter where we are on the earth, no matter where the moon is in the sky, and no matter the phase of the moon. The “rabbit” side is always the “front”, and the “upside-down bird” side is always the “back”.

Furthermore, if we were to draw another arrow at right angles to the first, it would always point towards the North Star in the sky. The moon has a steady, permanent “top”, but it is not the side facing “up” away from the ground, it is the side facing the North Star.

So the moon does have a “top” and a “bottom”, a “left” and a “right”, that are always the same, but we have to stop thinking about “up” and “down” compared to the ground. We have to start thinking about “north” and “south” in the sky. We can give four official names to four important sides of the moon, like “cardinal directions” here on the ground, but we have to think of directions in outer space. We can call the side of the moon facing the North Star the North Pole of the moon, and that's the side that we usually put at the top when we make maps. The opposite side is of course the South Pole. And the “Arrow Through the Moon” marks the Equator of the moon. The arrow follows the equator and points from the western to the eastern hemisphere of the moon, and from east to west in our local sky. (And if you reverse the arrow, then it points from west to east in our sky, in the direction that the moon passes through its phase cycle. It shows the direction that the moon travels as it orbits in space around us. But that's going off on a tangent…)

Major Features Through a Telescope

Imagine Galileo's wonder when he observed the moon through a telescope for the first time, and saw that it was not smooth. The dark areas are remarkably smooth and flat, like they are full of water, but everywhere else there were wondrous landforms. The moon has mountain ranges, and bumpy plains, and even a few cliffs and a few valleys. Galileo was the first to see that the moon is truly another world. You can see these beautiful things, too, with any small telescope, or a good pair of binoculars, or maybe even a camera with a zoom lens. After you've found a few beautiful mountains and craters on the moon, you may want a detailed map to help you explore. Let's start by giving some official names to the major landmarks, and then we can worry about a detailed map after that.

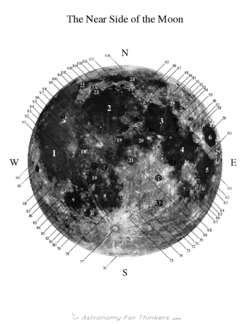

The following downloadable handout shows the full moon oriented with the north pole at the top (as most full moon photos do), and with the “Arrow through the Moon” (i.e., the equator) pointing from left to right, and it gives the official names for the larger features of the moon.

The first people to give official names to the dark smooth areas called them “seas”, or “maria” in Latin, and the names stuck. (When giving official scientific names to things, earlier scientists usually used the closest thing they had to a universal language: Latin.) The official name for the huge blank area between the “head” and the “upside-down bird” is Oceanus Procellarum, or the “Ocean of Storms”. The official name for the “head” is Mare Imbrium, or the Sea of Showers. The three blobs that make up the “snowman” or the “rabbit” are officially called Mare Serenitatis (Sea of Serenity), Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility), and Mare Fecunditatis (Sea of Fertility), and the “Demon Eye” is officially known as Mare Crisium (Sea of Crises). The thumb of the “Lego Hand” was named for its position in the face of the moon: Sinus Medii, or the Bay of the Center. (There's also a Mare Marginis, or Sea of the Edge, but that's so far around the side that it's hard to see.) The muddled, mingled darkness in the lower left is officially named as two more seas: Mare Nubium (Sea of Clouds) and Mare Insularum (Sea of Islands).

I have also included the names of several craters. Most people can't see these without a telescope, but they stand out in almost any picture of a full moon, and they are all named after major figures in the history of astronomy. If you are a teacher, and none of your students have asked you about that bright star-like thing near the bottom, that's the crater Tycho, named after Tycho Brahe. The three prominent craters within the Ocean of Storms are Aristarchus, Copernicus, and Kepler. Plato and Aristotle weren't strictly astronomers, but they stand as a pair of opposed giants in the intellectual history of Western Civilization, and I like the nice symmetry displayed by the two craters named after them. (To me, they evoke the way Plato and Aristotle are displayed in the classic painting The School of Athens by Raphael. Someday I'll find out who named those two craters originally and find out if it was a deliberate choice, or if it is just my personal imagination.)

Except for the craters, you can identify most of these features any time you see the full moon in the night sky, and you can find all of them easily in binoculars or a small telescope.

Once you are familiar with the face of the moon, like an old friend in the sky, you can figure out all sorts of things whenever you see it. A fun exercise might be to look at photographs of the moon near the horizon, and to see if you can solve the puzzle of which way the photographer was facing when he took the picture. (Imagine the “arrow through the moon”, and see if it is pointing up or down. If it is tilted upwards and to the right, then the moon is rising, and the photographer was facing east. If it is tilted down and to the right, then the moon is setting, and the camera was pointed west. If the moon is full, you can also tell the time of day, because the full moon always does the opposite of the sun. If the arrow through the moon is pointing to the left, then the picture was either taken in the southern hemisphere, or somebody flipped the photo backwards.) Sometimes, you can tell that a photograph is obviously fake. For example, if you see a photo of a moon very close to the horizon, but the arrow is pointing sideways, you can tell that somebody just pasted a “normal” photo of a full moon over a background picture. (Unless you live near the poles, the arrow through the moon should always be tilted when the moon is near the horizon.) Once or twice I have come across a photo of the moon that was backwards, with the eagle-head-rabbit sequence going counterclockwise instead of clockwise. Someone had obviously flipped the photo in Photoshop. Once I was watching a scene in a science fiction movie taking place on a foreign planet, and showing two moons in the sky. But the faces of both moons were identical to the face of earth's moon, so they obviously just copied and pasted an image of the earth's moon, instead of bothering to draw new ones.

A Map of the Moon

Finally, now that we have our bearings, we can go hunting for smaller and more remarkable things. We can explore the moon as we might explore the earth. We can navigate through the details in a map of the moon in the same way we might navigate through a map of the world. In the case of the moon, we can find these places on the map, and then try to visit them on the real moon with a telescope or even a pair of binoculars. It could be like geography class for the moon.

The following is a detailed printable map of the moon, with around a hundred features identified. What can you find?

Craters are traditionally named after famous people, and the most prominent are generally named after astronomers. (Although two of the most important names in the history of astronomy, Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton, were given to rather nondescript craters near the edges of the moon. You can't even see them on this map.) If you go exploring with a telescope, you might notice that some craters, like Plato, are dark and flat in the middle, almost like perfectly round maria. Others, like Tycho, have one or several peaks right in the center of the crater. This happens so often that scientsts give them a special name: “central-peak craters”. You might also be interested to know that our modern official naming system evolved from an original system developed by Giovanni Battista Riccioli, who was later honored with his own crater near the western edge of the moon.

I have emphasized the sites of manned lunar landings by circling their numbers. Stare at them for a few moments and see if you notice any pattern in how they are distributed.

If you were planning to land your vehicle on another world for the first time, where would you want to aim? Flat land or mountains? Notice that the first three missions to land on the moon were all aimed at flat land. They were also all along the equator, because that required less maneuvering and gave a greater margin for error. After the engineers and explorers grew more confident with their equipment and procedures, they grew more ambitious: Missions 15, 16, and 17 landed off-equator on rougher terrain. (You might also notice that every mission landed on the near side of the moon, and not too far from the center, at that. The Apollo astronauts did get to see the moon's secret on the back side as they orbited around the moon, but they never landed there. You can probably figure out why for yourself.)

One final note: If you want to explore the moon with a telescope, which phase would be the best to explore? Many people answer that the best time is when the moon is full, because that's the only time when the entire surface is visible. But this is also the time when it is “noon” on the moon, and there are no shadows, or only short ones, and the strongest contrasts will simply be due to the color of the soil. This is why I didn't bother to label many craters in the Southern Highlands. It is chock full of them, but you just can't see them very well when the moon is full. You will probably be much more impressed by your view through a telescope if you wait for a different phase, and then examine the moon near the edge of the dark side. This is where the shadows of mountains and craters are deepest, and the vertical contours of the moon really jump out at you. This is where the view through a telescope can be stunningly beautiful.